Mastering is often seen as audio production’s mysterious black art. We’d like to take a moment to pull back the curtain on mastering to reveal what the craft genuinely entails. If you’ve developed your ears to the point that you can mix a track, you can learn to master as well; it requires a different but very related skill set.

What is mastering, anyhow?

Mastering is the final step in the audio production process, where the final mix of a song is polished and prepared for publishing and duplication. It includes:

- Track order, pauses, and crossovers

- Application of dynamics processing and other effects to ensure consistent, satisfying tone, loudness, and dynamics across an entire collection of songs (an album or EP)

- EQ processing to ensure that the music sounds cohesive and professional across various playback systems. (Vinyl in particular has specific EQ requirements.)

- Frequency-dependent panning is also common to center bass frequencies in the stereo image.

- Addition of metadata, such as ISRC codes and album information for royalty tracking.

Because mastering is concerned with objectively measurable hard data like loudness values and dynamic ranges, it can be argued that mastering is more on the science side of the Recording Arts and Sciences.

Mastering can be done using purpose-specific analog hardware or done completely in-the-box in software… It’s also common to use a mix of both analog and digital tools; commonly known as hybrid mastering.

Listening and note taking

The mastering process typically begins with a thorough listening session. The mastering engineer carefully evaluates the mix, identifying any issues such as frequency imbalances, dynamic inconsistencies, or unwanted noise.

The listening environment is also a critical factor of the mastering process. Much time and attention (and expense!) is frequently dedicated to setting up a mastering room, including acoustic treatment, ideal monitor placement, and a room-corrected EQ curve to keep the playback as flat as possible.

Reference tracks are very useful at this stage – the mastering engineer will frequently switch back and forth between listening to the artist’s work and a finished, mastered reference track in an effort to match the sound of the reference track. It’s commonplace for the mix engineer or artist to provide reference tracks as a guide for the intended tonal qualities of the finished product.

This critical listening stage is essential for developing a game plan for subsequent technical adjustments. The engineer will often take notes and communicate with the mixing engineer to understand any artistic intentions or specific concerns that need addressing. For example, some mixes may use noise creatively, while in others the noise may well be undesirable. Best for the mastering engineer to check in with the mix engineer and artist in cases like these.

EQ

The mastering engineer employs EQ to balance the frequency spectrum, ensuring that no particular frequency range is overly dominant or lacking. This step can involve subtle boosts and cuts to enhance clarity and presence. For instance, adding a slight boost in the high frequencies can add brightness and air, while cutting muddy frequencies in the lower midrange can clean up a mix and help vocals render with greater intelligibility.

Here’s a look at a nuanced EQ curve in a bass-heavy rock mix in Softube Flow’s EQ plug-in. Note that there’s no adjustment greater than +/- 1.5 dB aside from the ultra-low end roll-off to prevent non-musical rumble in subwoofers.

Dynamics and Loudness

Dynamic range is a way of describing the difference between a track’s quietest and loudest moments. Think of it this way – you may have heard a song that has vocal elements that are whispered in one part of the song and screamed in another. If the loudness of these elements were the same of that as a person whispering and screaming in a room next to you, you would constantly be turning up the volume to hear the whisper and down to duck the screams. Artfully tailoring the dynamic range of a track allows both loud and soft elements to co-exist in the same track; both at a comfortable listening volume.

Dynamic range is determined by calculating the ratio between a track’s LUFS (more on that later) and peak level, which is the single loudest element in a given song.

Dynamic processing is applied in the mastering stage to achieve a consistent loudness level and to prevent distortion. Dynamic range control is typically achieved through compression and limiting. Compression is used to control the dynamic range of the audio, making quieter parts more audible and reducing the peaks’ loudness for a more consistent and polished sound that prevents the listener from reaching for the volume knob.

Limiting, a more extreme form of compression, is applied to ensure that the track’s overall volume is at an optimal level without causing distortion. Proper use of compression and limiting ensures that the track sounds full and punchy while maintaining musicality. Unlike a compressor, a Limiter has a hard ceiling which ensures the source material never goes above digital 0; limiters are often placed at the end of the mastering signal chain.

A very popular tool in mastering chains is a multi-band compressor, which is capable of applying various compression ratios and curves to different frequency bands independently of one another.

A multi-band dynamics processor in Softube Flow, modeled after the classic Tube-Tech Stereo Multiband Compressor.

This is also the stage where a track’s loudness can be shaped. Loudness is a subjective measure of how strong a sound is perceived, from quiet to loud. It’s based on the sound’s intensity, frequency, and duration.

Generally speaking, a track’s loudness is related to dynamic range – the amount of distance between the quietest sound in a song and the loudest. In mastering, loudness is commonly maximized so that a track sounds competitive and powerful when played alongside other songs,while maintaining a volume level consistent with other songs.

That said, too much loudness can result in significant distortion and reduction of dynamic range. Some engineers/labels/artists feel it’s worth this compromise in order for their tracks to compete in the musical landscape. Others hate it. As such, loudness is a controversial and complex topic that is beyond the scope of this article. Google the “Loudness War” for more detailed conversations on loudness.

Loudness is typically measured in LUFS, or “Loudness Units Full Scale,” a unit of measure that describes the average volume level over time. LUFS are measured in the negative A low LUFS rating such as -16 indicates a large difference between the quietest and loudest parts of a track; a high LUFS rating such as -6 indicates that the whole song is playing back at a very consistent level.

Finding the right LUFS value for a song can be a balancing act. Too low of a dynamic range (high LUFS) can result in a track that doesn’t sound very exciting. Too high of a dynamic range (low LUFS) can result in a song with passages that are difficult to hear at the listener’s desired volume setting.

Target LUFS standards for streaming services vary a bit, but are generally around -14 LUFS.

For some fantastic info on true peak limiting and metering, dithering, oversampling, and more, check out this excellent piece from Softube.

Stereo Image

Stereo imaging is also adjusted during mastering to ensure that the spatial characteristics of a mix are balanced and pleasing. The mastering engineer can widen the stereo field, making a track sound more expansive and immersive. Conversely, if a mix has phase issues or an overly wide stereo image, the engineer may narrow the stereo field to ensure mono compatibility and focus.

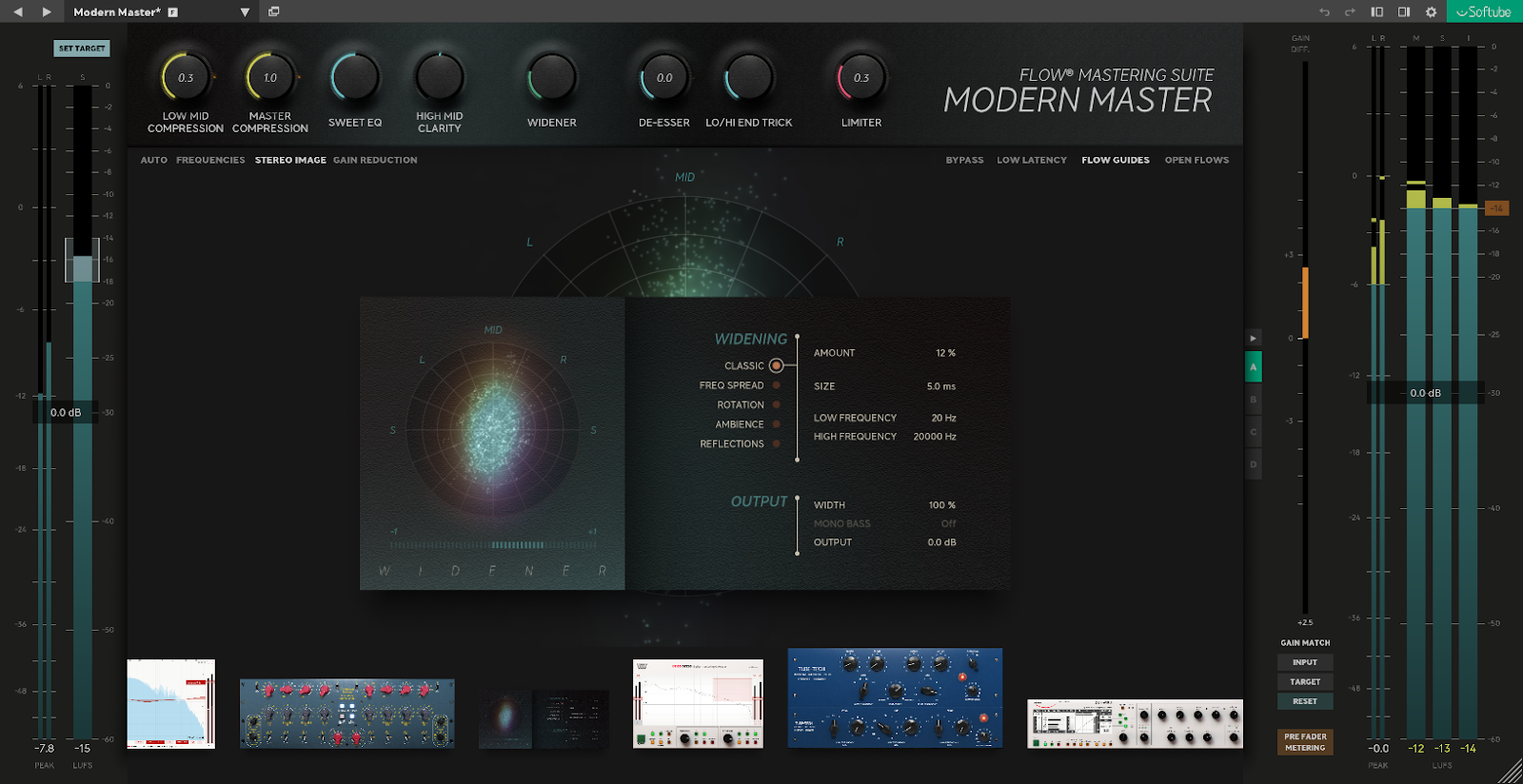

Here we see the stereo image of the same song rendered in a 2D phase meter of the Widener plug-in of Softube Flow. Options for widening, mono bass, and frequency crossovers are available.

Vinyl, in particular, has specific needs in width processing – if too much bass is panned too hard to one side, the needle can actually get tossed out of the groove! Mastering for vinyl typically involves stereo image processing that centers all frequencies below around 100 Hz.

Sequencing

In addition to the above technical adjustments, mastering also involves sequencing and spacing for albums or EPs. The mastering engineer enacts the order of tracks specified by the artist, and the length of silence between them, creating a cohesive flow from one song to the next. Crossfades between songs will be implemented at this stage as well.

Because the sequencing process considers the musical dynamics and emotional arc of the album, it’s vital for maintaining the listener’s engagement and delivering a seamless listening experience.

Metadata and Distribution

The mastering engineer provides the final masters along with any necessary metadata, such as ISRC codes and album information, which are essential for digital distribution and royalty tracking.

Once the metadata is completed, the final master is created in the appropriate format for distribution. This could include preparing versions for digital platforms, CD production, and vinyl pressing. Each format has specific technical requirements and limitations, and the mastering engineer ensures that the final product meets these standards.This is a rich topic worthy of its own article; we’ll dive into that next time!

Should I master my own records?

Sure, you can, with practice, but there are benefits beyond the mastering work itself in having someone else master your tracks. Sending your tracks to an experienced mastering engineer also ensures that a second pair of ears hear your productions – and they may hear issues in your music that you didn’t and offer feedback to help your mixes.

Similarly, even the best writers submit their work to an editor rather than editing the work themselves.

Ready to master mastering?

Mastering can be hard, but the tools for mastering are getting better and more intuitive all the time. If you would like to try out mastering for yourself, consider Softube Flow. Flow is a fantastic alternative to hiring a mastering engineer, and gives you more control over your own sound than questionable online AI mastering tools.

Flow includes its own sub-plugins that cover all the different elements of mastering outlined above – EQ, Dynamics, etc. – and arranges them into easily-understood mastering chain presets and macro controls made by some of the world’s most prestigious mastering engineers. With Flow you can access and edit these mastering chains easily without having to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on the equipment or thousands of hours learning from scratch.

Flow isn’t just a great mastering tool – it’s a great learning tool. Flow users report that they feel it has taught them what to listen for and adjust, developing their ears to hear potential adjustments in their tracks that they didn’t consider previously.

Unlike outboard hardware processors, Flow’s fantastic GUI delivers real-time visual feedback to your parameter changes, allowing users to learn both by ear and by eye… helping them to more quickly understand the correlations between what they are doing, seeing, and of course most importantly – hearing.

As of July 1, 2024, Softube Flow is included with all hardware products from Black Lion Audio. All you have to do is register your hardware to get a 30-day subscription to Flow. This offer is also available to existing owners of Black Lion Audio hardware!